Ann M Steffen, PhD - University of Missouri - St. Louis

Synchronous (live) psychotherapy delivered via video conference or telephone-only can be an effective way to provide CBT to adult clients across the lifespan, including CBT with older adults. There is a longstanding recognition that many prospective mental health clients experience physical barriers that can be addressed through telemental healthcare. Those living in rural communities are especially unlikely to have easy access to in-person psychotherapy with a local provider. Others live with a range of acute and chronic physical health conditions that limit mobility and make attending weekly therapy sessions very difficult. Poor access to transportation compounds these challenges for many. It is important for us to recognize that none of these barriers are new. The identified need for, interest in, and research on telephone-based and video-conferenced psychotherapy are all well-established (Riper & Cuijpers, 2016). Many healthcare systems across the globe and within the US have decades of experience in providing live/synchronous teletherapy to clients (Myers & Turvey, 2012).

For most psychotherapists, however, the initial COVID-19 lockdown created their first, and very sudden, experience with providing therapy by videoconference and/or telephone. Along with coping with other aspects of the pandemic, we lived through a wide range of challenges with this pivot away from in-person sessions. Some of these difficulties have remained for therapists who include teletherapy within their clinical practice. As we reach the four-year anniversary of the 2020 initial lock-down within the United States, it is helpful to address ongoing concerns by examining lessons learned, especially in CBT practice with older adults who are living independently in the community. Because of the complexities involved, this article will not focus on the added challenges of clinical work in the context of assisted living or skilled nursing care (interested readers are referred to resources provided by Psychologists in Long Term Care; www.pltcweb.org).

Evidence Base - How confident can we be regarding our evidence base for using telehealth to provide psychotherapy?

Does it work? Meta-analytic reviews have evaluated both the efficacy (randomized controlled trials) and effectiveness (evaluations in routine clinical settings) of both video-conferenced and telephone-based psychotherapy compared to in-person sessions. These reviews have generally concluded that client outcomes are similar among delivery formats for clients across the adult lifespan and across a range of presenting concerns (Lin et al., 2022; Varker et al., 2019). This “equal outcomes across delivery formats” conclusion has been echoed in reviews for CBT interventions specifically (Nelson & Duncan, 2015), CBT for depression (Cuijpers et al., 2019) and with older adults (Freytag et al., 2022; Gentry et al., 2019). Individual research studies focused on older adults suggest comparable findings. Positive outcomes have been reported for telephone-delivered CBT for older, rural Veterans with depression and anxiety in home-based primary care (Barrera et al., 2017), telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults (Choi et al., 2014), and telehealth CBT for depression and insomnia in ethnically diverse older adults in rural south (Scogin et al., 2018). Outcomes for telehealth interventions with dementia family caregivers have also been favorable for a range of psychosocial outcomes including depression (Steffen & Gant, 2016).

Is teletherapy acceptable to clients? A rather important question has been whether older psychotherapy patients will accept the use of remote technology to engage with their clinician. Although some aging individuals expressed initial hesitance before beginning use in a qualitative study, most concluded after participating in a telehealth intervention that they appreciated the convenience and were able to feel emotionally connected with their provider (Choi et al., 2014). Beyond qualitative interviews with service recipients, data on attendance patterns and attrition can also answer questions about acceptability. Clients receiving telephone-based CBT have the very lowest attrition rates (i.e., are less likely to drop out of therapy prematurely), followed by those participating in video-conferencing sessions, with attrition rates highest for in-person CBT (Cuijpers et al., 2019; Cuthbert et al., 2022).

Common Challenges

Despite this evidence, it is clear that as CBT clinicians, we continue to experience a range of issues in our psychotherapy practices that involve video-conferencing or telephone-only sessions. Most of these challenges occur in telehealth CBT sessions with clients across the lifespan. These include a host of familiar concerns including spotty wifi and connectivity issues (or complete lack of internet access), reliance on smart phones leading to screens too small for use of printed materials or screen sharing, distractions in the home such as other people, pets, tv; increased client expectations for last-minute rescheduling of sessions, desire for more session time devoted to supportive counseling, gauging clients’ engagement in therapy, and especially challenges in assigning and reviewing between session practice forms (aka “homework’).

Some clinicians describe concerns in their teletherapy CBT practice that are perhaps not unique to older adults but may occur more frequently. Certainly, age-associated sensory changes in vision and hearing are something that we accommodate for, whether sessions are held in person or via a different delivery format; holding sessions by video conference or telephone-only can compound these challenges. Most older adults are both familiar with and routinely use a range of technologies (Greenwald et al., 2018), yet may require more frequent reminders and additional time for managing some of the details of videoconferencing (logging in procedures, turning on video and adjusting audio levels, hiding self-view). Repeated use of a small set of printed handouts and between-session worksheets can be quite useful (Steffen et al., 2021). Importantly, anxiety about difficulties that arise when using video conferencing technologies and software can provide opportunities for therapeutic responding, including problem-solving, exposure strategies, along with other CBT interventions to address the challenges of telehealth that are associated with distress.

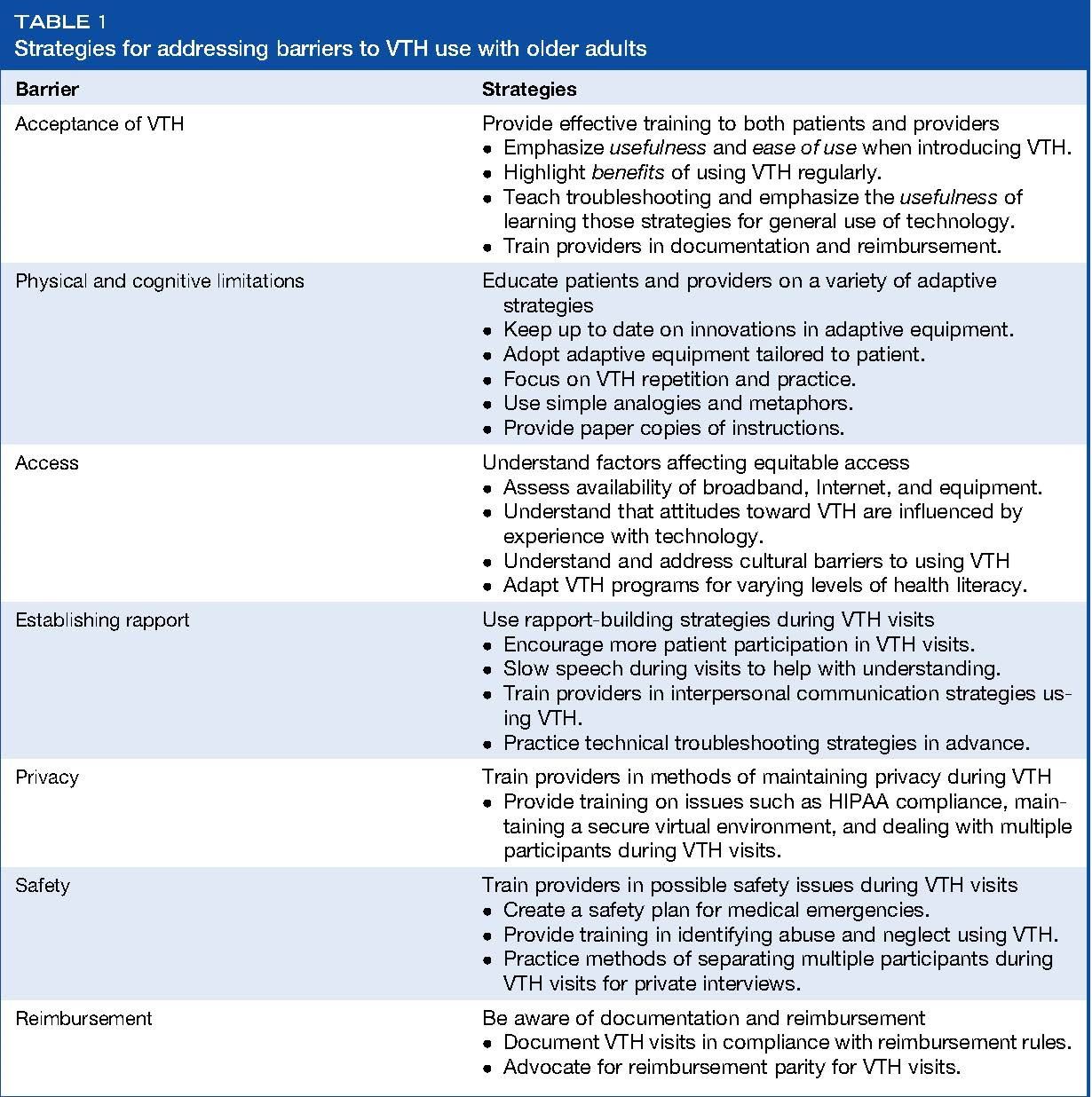

Table 1 shown below, from Freytag et al. (2022) provides a nice starting point for thinking about your own ways of addressing some of these concerns.

Table 1 from Freytag et al (2022). Reproduced with permission.

Note: VTH refers to Video Telehealth

Concluding Comments

There are now a variety of resources and tips available for CBT therapists who would like to improve the impact of their telehealth sessions with older adults. These include strategies to manage procedural aspects of telehealth sessions, develop and maintain therapeutic rapport, and enhance therapy effectiveness with older adult clients.

Barrera, T. L., Cummings, J. P., Armento, M., Cully, J. A., Bush Amspoker, A., Wilson, N. L., & ... Stanley, M. A. (2017). Telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for older, rural Veterans with depression and anxiety in home-based primary care. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal Of Aging And Mental Health, 40(2), 114-123. doi:10.1080/07317115.2016.1254133

Choi NG, Hegel MT, Marti N, Marinucci ML, Sirrianni L, Bruce ML. (2014), Telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed low-income homebound older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014 Mar;22(3):263-71. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318266b356.

Choi NG, Wilson NL, Sirrianni L, Marinucci ML, Hegel MT. (2014), Acceptance of home-based telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults: qualitative interviews with the participants and aging-service case managers. Gerontologist, 54(4):704-13. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt083.

Cuijpers, P., Noma, H., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A., & Furukawa, T. A. (2019). Effectiveness and acceptability of cognitive behavior therapy delivery formats in adults with depression: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(7), 700-707.

Cuthbert, K., Parsons, E. M., Smith, L., & Otto, M. W. (2022). Acceptability of telehealth CBT during the time of COVID-19: evidence from patient treatment initiation and attendance records. Journal of behavioral and cognitive therapy, 32(1), 67-72.

Freytag J, Touchett HN, Bryan JL, Lindsay JA, Gould CE. Advances in Psychotherapy for Older Adults Using Video-to-Home Treatment. Adv Psychiatry Behav Health. 2022 Sep;2(1):71-78. doi: 10.1016/j.ypsc.2022.03.004. Epub 2022 Sep 9. PMID: 38013747; PMCID: PMC9458515.

Gentry, M. T., Lapid, M. I., & Rummans, T. A. (2019). Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(2), 109-127.

Greenwald, P., Stern, M. E., Clark, S., & Sharma, R. (2018). Older adults and technology: In telehealth, they may not be who you think they are. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 11(1), 2–4.

Lin, T., Heckman, T. G., & Anderson, T. (2022). The efficacy of synchronous teletherapy versus in-person therapy: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000056

Luxton, D. D., Nelson, E. L., & Maheu, M. M. (2022). A practitioner's guide to telemental health: How to conduct legal, ethical, and evidence-based telepractice. 2nd edition. American Psychological Association.

Myers, K., & Turvey, C. (Eds.). (2012). Telemental health: Clinical, technical, and administrative foundations for evidence-based practice. Newnes.

Nelson, E.-L., & Duncan, A. B. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy using televideo. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 269–280. https://doi-org.ezproxy.umsl.edu/10.1016/j.cbpra.2015.03.001

Riper, H., & Cuijpers, P. J. (2016). Telepsychology and eHealth. In J. C. Norcross, G. R. VandenBos, D. K. Freedheim, & R. Krishnamurthy (Eds), APA handbook of clinical psychology: Applications and methods, Vol. 3, (pp. 451-463). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, xvi,

Scogin, F., Lichstein, K., DiNapoli, E. A., Woosley, J., Thomas, S. J., LaRocca, M. A., Byers, H. D., Mieskowski, L., Parker, C. P., Yang, X., Parton, J., McFadden, A., & Geyer, J. D. (2018). Effects of integrated telehealth-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression and insomnia in rural older adults. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(3), 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000121

Steffen, A.M., Dick-Siskin, L., Bilbrey, A., Thompson, L.W., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2021). Treating Later-Life Depression: A Cognitive Behavioral Approach Workbook. 2nd edition, 358 pages. Treatments that Work Series; Oxford University Press.

Steffen, A. M., & Gant, J. R. (2016). A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers. International Journal Of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(2), 195-203. doi:10.1002/gps.4312

Varker, T., Brand, R., Ward, J., Terhaag, S., & Phelps, A. (2019). Efficacy of Synchronous Telepsychology Interventions for People With Anxiety, Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Adjustment Disorder: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Psychological Services, 16(4), 621-635.